We begin our journey with a brief exploration of French cuisine, perhaps some of the most famous in the world. Both for my own sanity while cooking, and because I'm more interested in the commonplace dishes in each country, I don't intend for this blog to be a review of fine dining.

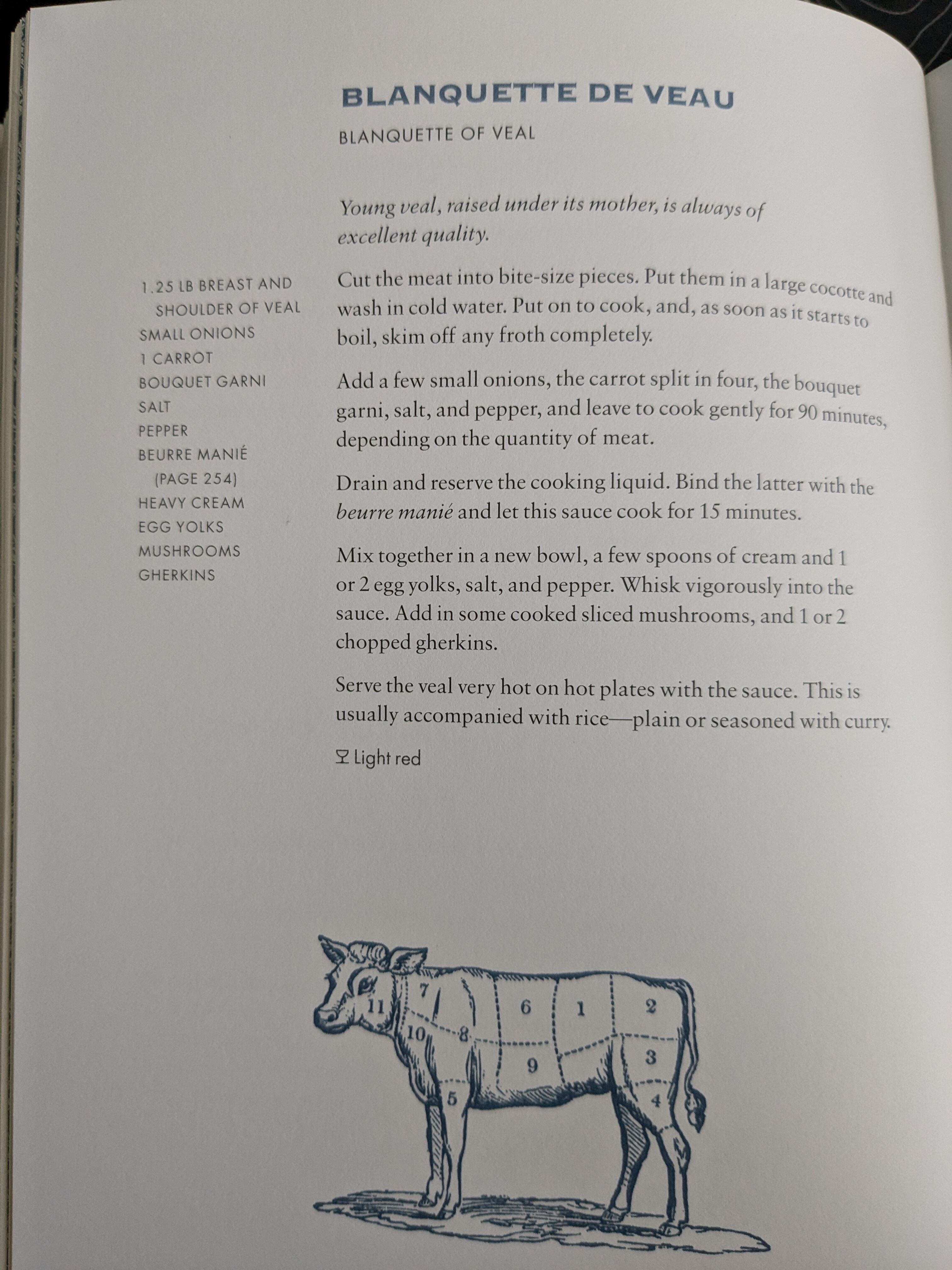

This week's dish, blanquette de veau -- "blanquette" meaning a white dish, "veau" meaning veal -- is a stew originating in Normandy. Wikipedia describes it as being "among the most popular meat dishes in France."

As the name suggests, this stew is typically made with veal, the meat of young cows. Veal is much tamer than beef, more tender, and lighter in color. Like most popular dishes, there are many different recipes and techniques for making blanquette de veau. Some use lamb or poultry, some use vegetables such as leek or turnip.

The recipe I chose is by la Mère Brazier. Eugénie Brazier was a classical French chef. She was the first person in history to be awarded six Michelin stars, and is sometimes referred to as "the mother of French cooking." The recipe comes from her cookbook, The Mother of Modern French Cooking:

It's a surprisingly easy dish to pull together, and -- like most popular dishes -- fairly affordable.

It is at this point, however, that I must acknowledge that I live in Indiana, not France. I wasn't able to get my hands on veal in time, so I substituted a standard stewing cut of normal beef. (I've since decided that lamb would have been a closer substitute, but that's water under the bridge.) The recipe also calls for "Small Onions," which I interpret to mean pearl onions. For those, I had to substitute a small sweet onion, quartered.

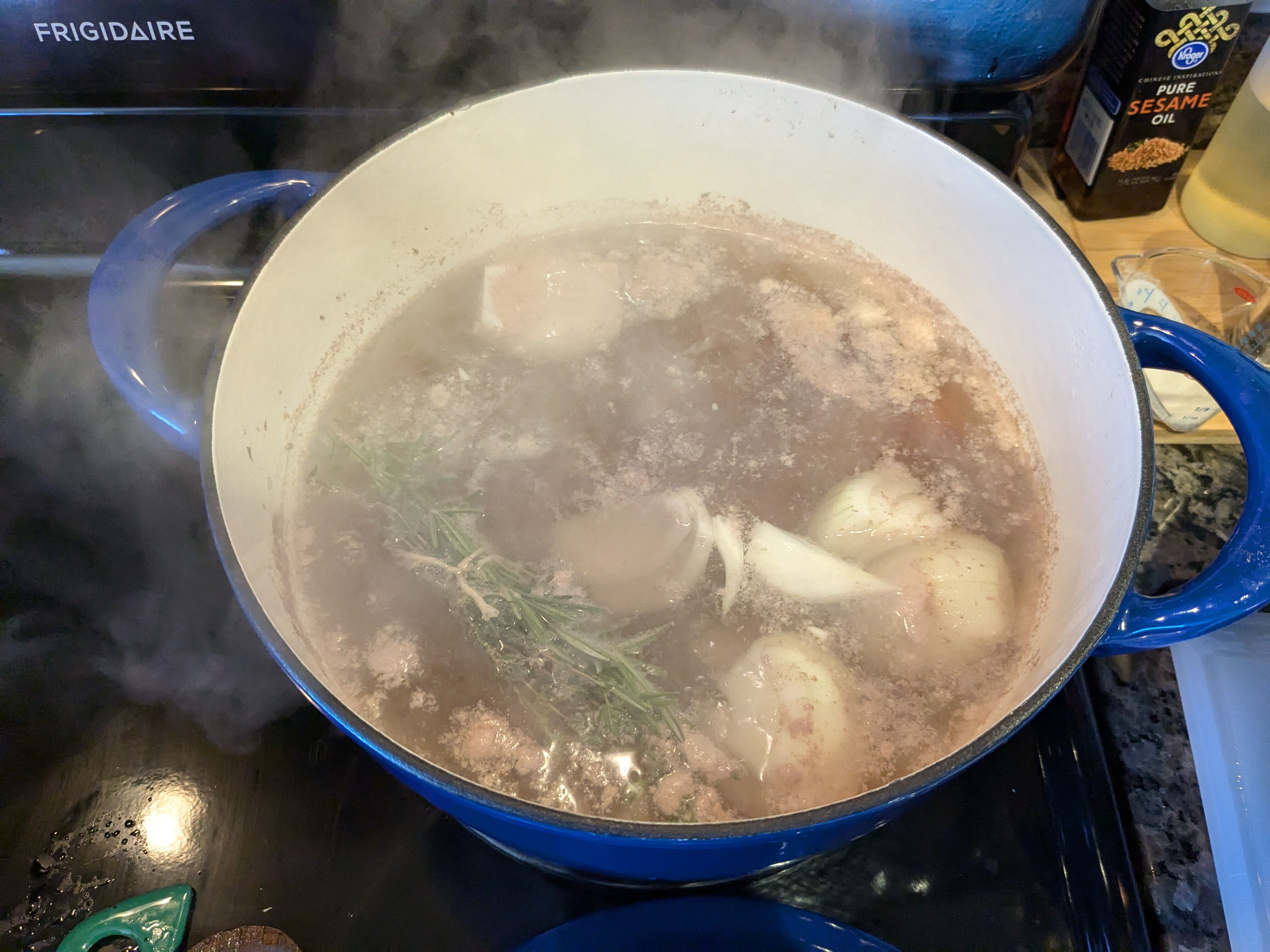

The recipe begins by bringing the meat to a simmer on its own, skimming off the scum. This is, in my opinion, by far the most annoying step in the recipe. I'd recommend doing this with a fine-mesh spider if you have one, but I don't.

After the scum has mostly subsided, add in the hard veg and bouquet garni (of thyme, rosemary, and bay leaves) and simmer for 90 minutes. Brazier's recipe assumes you're using veal, which is more tender, so I found it needed to simmer for a bit longer to produce tender beef.

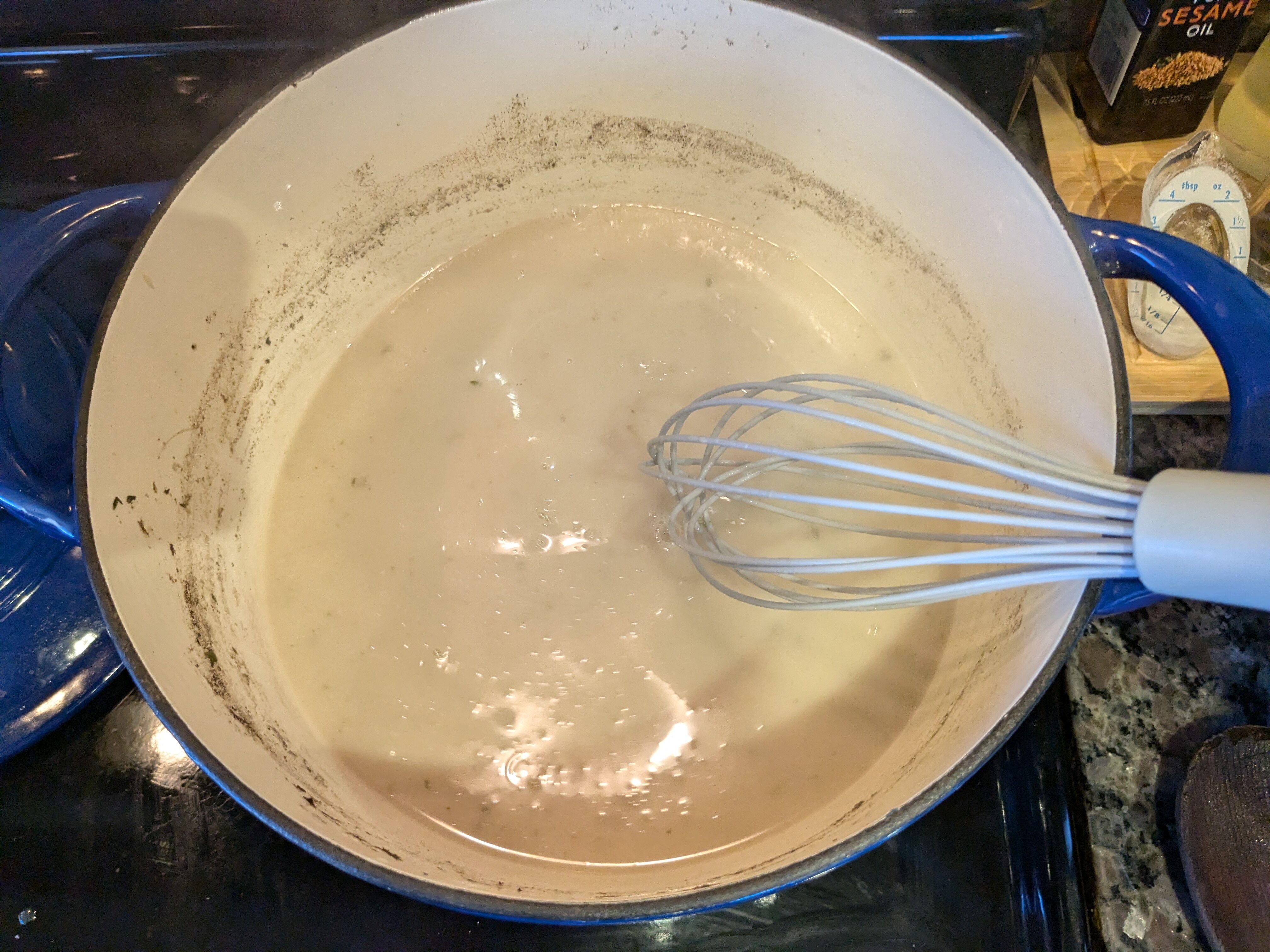

Toward the end of the cooking time, the recipe calls for a buerre manié (what I would've called a roux). The recipe says to prepare this, then mix it directly into the cooking liquid, then add a mixture of egg and cream for richness. I departed from the recipe a bit here to add some of the liquid to the buerre first to prevent clumps. I also tempered the egg mixture w/ the cooking liquid.

After a bit more cooking (Brazier warns you not to simmer it), I stirred the meat and veg back in, and added salt and the cooked mushrooms. I sauted these lightly. Then, a curveball: stir in some chopped gherkin.

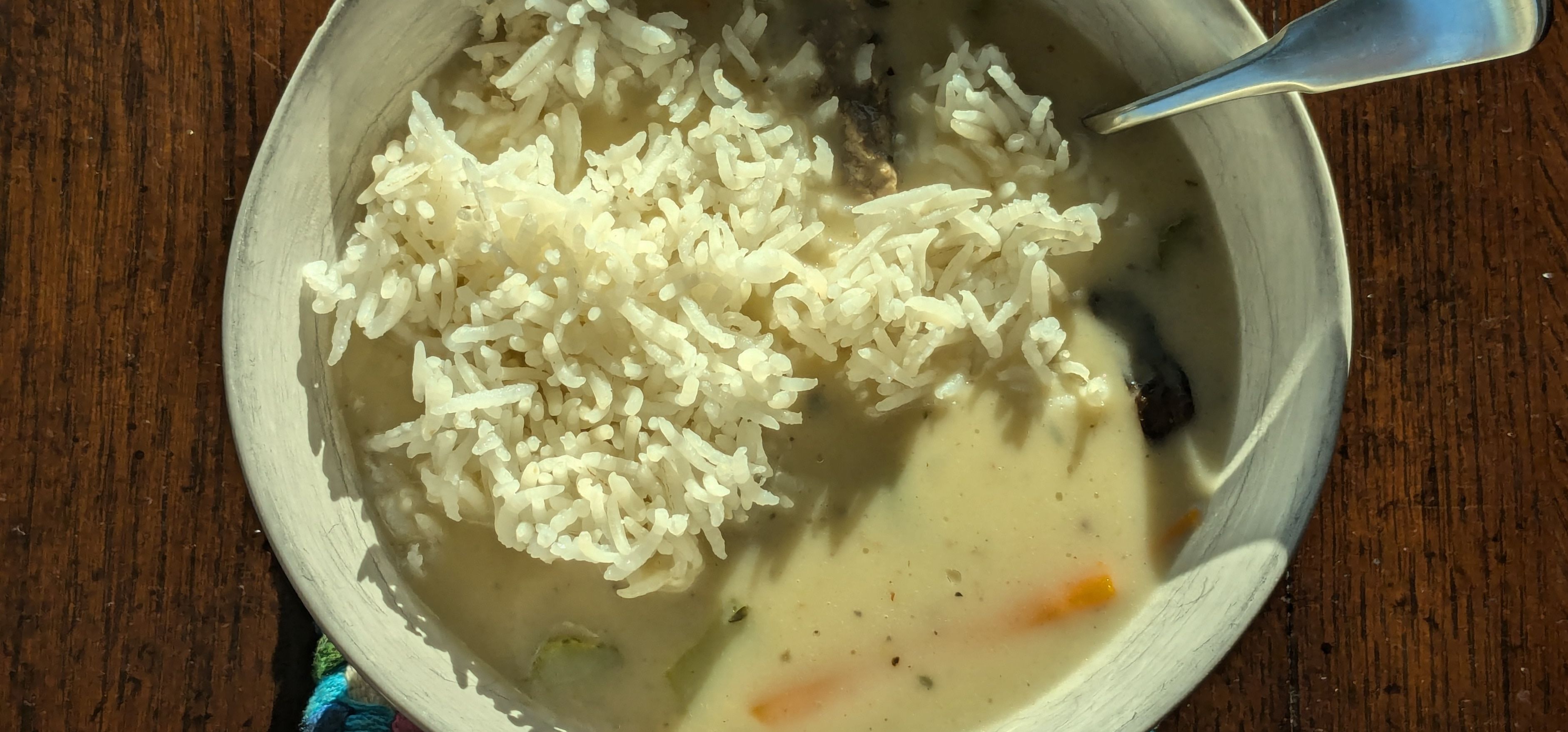

The stew was rich and creamy, but subtle. It tasted like true comfort food -- warm, hearty, but not overwhelming. I was skeptical about the gherkin at first, but I think it works. It provides an occasional burst of acidity and brightness in what is otherwise a very rich dish.

Because the dish is so subtle, I found it to be very sensitive to under-seasoning. Despite adding salt and pepper when cooking initially, I had to add quite a bit more salt at the end. (For this style of dish I instinctively reach for Maggi seasoning, but that seemed offensive...)

I'm excited to try this dish again in the future, probably with the addition of some of the veg I saw in other recipes, such as parsnip or leeks. It's probably sacrilegious, but I also think something green like frozen peas would be quite nice.

All images in this post were taken by me, except the one of la Mère, which I sourced from here, with attribution.

I borrowed The Mother of Modern French Cooking from the fantastic Indianapolis Public Library.