We continue our exploration of Ethiopian cuisine this week with another dish for special occasions: zilzil tibs. Tibs, generally, refers to grilled/pan fried meat, sometimes cooked with vegetables. From Yohanis Gebreyesus:

Zilzil refers to meat that has been cut into long strips using a technique that unfurls a chunk of meat into a somewhat imperfect strip.

The zilzil is finished in and served with awaze dipping sauce, a blend of honey wine and berbere spice. Along with this, we have gomen, simply sautéed collard greens. According to Yohanis, the gomen is often a side dish in a larger platter.

As you can see, we've returned to Yohanis Gebreyesus's excellent "Ethiopia: Recipes and Traditions From the Horn of Africa" for this week's recipes.1

As a westerner, I was quite surprised to see collard greens pop up, since I associate them so strongly with the American South. Further research revealed that the collard green plant actually originated from what is modern-day Greece, so its appearance in Ethiopian cuisine makes sense.2

I found the berbere at my international grocer. Of note, I substituted homemade ghee in place of the niter kebbeh and added in a tiny amount of the missing spices.3

First is the awaze, a mixture of berbere, honey, and white wine. While quite sharp at first, after sitting for 30 minutes or so, the spice blended with the wine much better. (A personal best for me: this was the first time I'd ever seen spices measured in cups.)

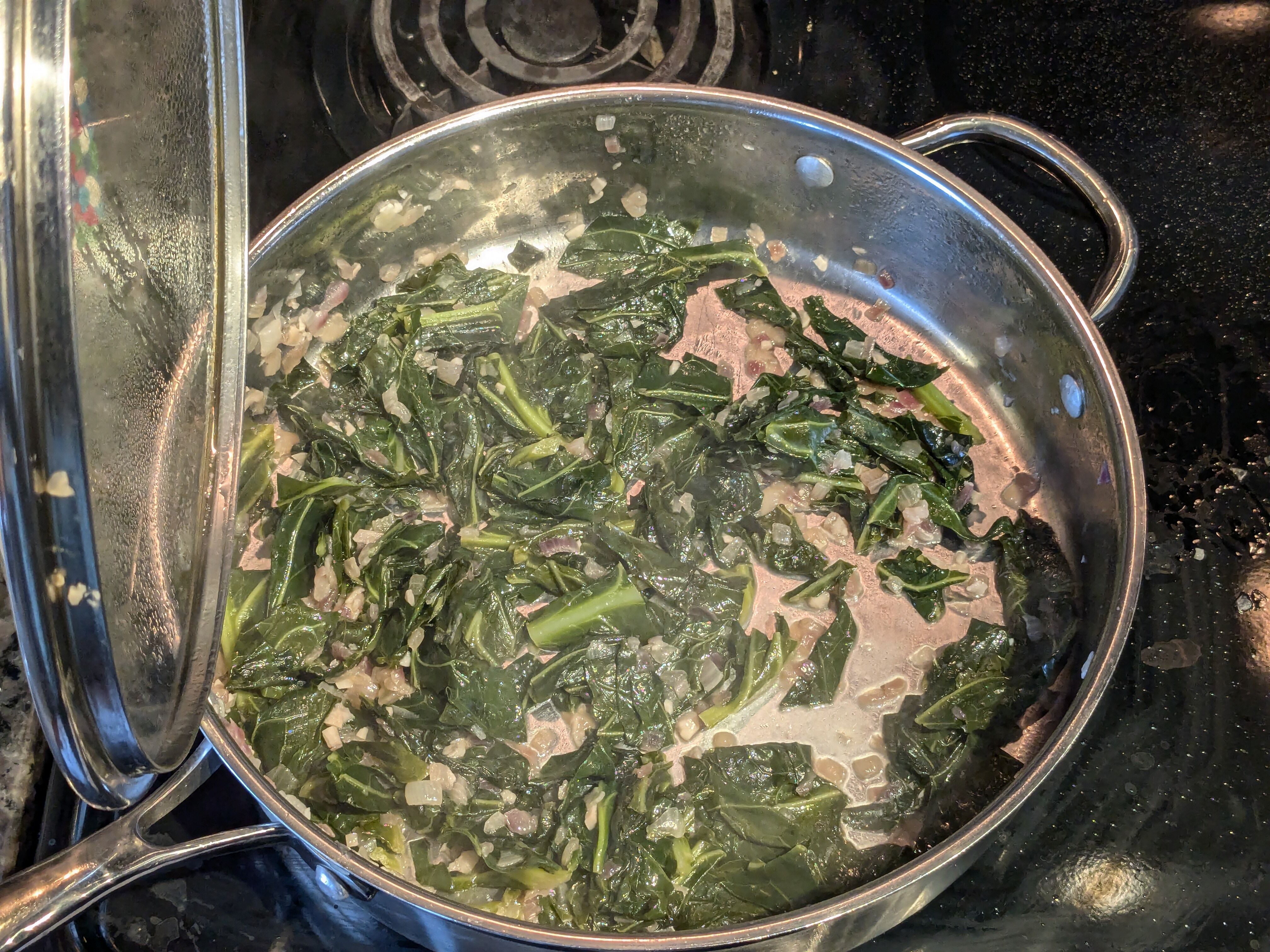

The collard greens are prepared by breaking down the leaves and washing them thoroughly. I prefer to remove most of the woody stem from the leaves. Then, we sauté an onion and some ginger/garlic.

Once the onion is soft, we add in the collard greens, cover, and cook them down until tender. The gomen is not supposed to be wet (as is customary with southern collard greens), but I did find I needed to add a few tablespoons of water occasionally to keep them from catching.4 This took about 30 minutes including time for the onion.

The beef is cut "into thin 1/2 inch wide strips" and fried in batches until brown and almost done. It is then removed and some of the awaze and niter kebbeh are added to the pan. The zilzil is then finished in the awaze.5

I served the zilzil and gomen with some of the reserved awaze and, of course, injera.6

I enjoyed this dish, though not quite as much as the doro from last week. The zilzil is extremely rich from both the inherent fried meat and the added niter kebbeh, so it takes the raw awaze well. I continue to revel at how central the injera is to the dishes we've tried. On its own, the awaze is quite spicy, and the zilzil is quite rich, but the strong sour taste of the injera balances the flavor.

As always, my technique has room to improve. I with I had cut the beef thinner and in shorter pieces. As is, it isn't bite-sized, so you have to bite through it. However, because the pieces are -on the thicker side, biting through it isn't trivial.

I would like to make tibs again in the future, but I'd probably try a different variation. "Tibs" as a dish is a bit like "steak" in its generality -- while it is a "dish," there are dozens of different variations. For example, this version by the fantastic Eden Egziabher, owner of the Makina Cafe in NYC.

--

All images in ths post were taken by me. I borrowed "Ethiopia: Recipes and Traditions From the Horn of Africa" from the fantastic Indianapolis Public Library.

Footnotes

-

Of course, these come from pages 45, 80, and 130. ↩

-

As we discussed last week, this is far from the only appearance of mediterranean plants and spices in Ethiopian cuisine. ↩

-

Waste not. ↩

-

Although this might not have been necessary had I left the lid on instead of taking it off to photograph the endeavor. So... your mileage may vary. ↩

-

A fact that, as Yohanis notes, is rather unusual since awaze is typically a dipping sauce served as-is. ↩

-

For more background on injera, see last week's post. ↩