Despite our previous explorations of meat-featuring special-occasion foods, Ethiopian cuisine is perhaps most famously known for its wide variety of vegan dishes. This is largely due to traditions of the Oriental Orthodox church, which bars the consumption of animal products during times of fasting.1

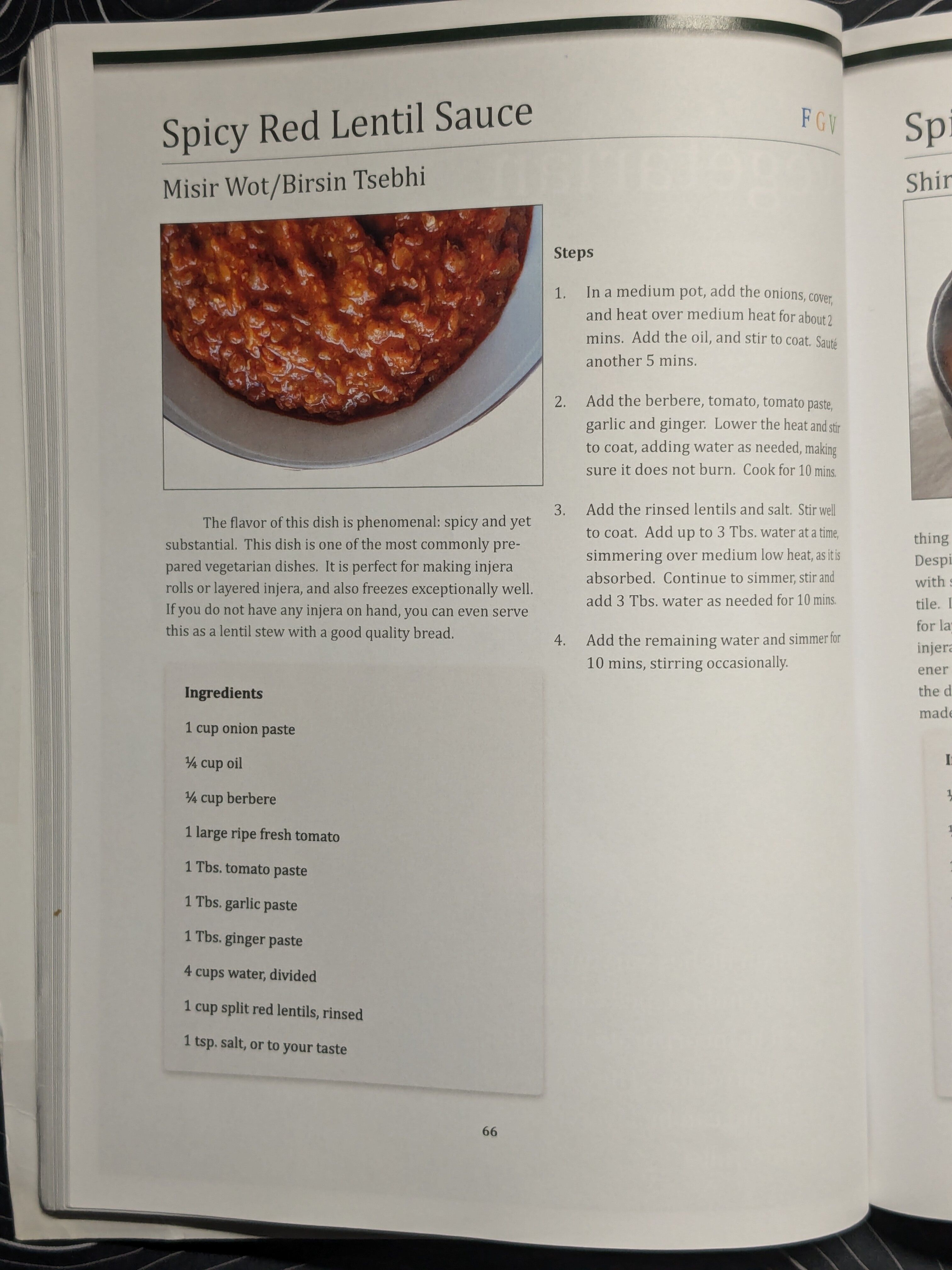

This week's dish is misir wot.2 Similar to our first foray, the doro wat, misir wot is a thick stew but this time made from lentils (red, traditionally)3 instead of chicken, and, according to today's recipe, is "one of the most commonly prepared vegetarian dishes."

This week I wanted to switch it up, so I'm using a recipe from "Auntie Tsehai Cooks: A Guide to Making Authentic Ethiopian and Eritrean Cuisine" by Tsehai Fessehatsion and Erin Peterson. According to her bio, Tsehai is a traditional Ethiopian cook who grew up learning from her mother. I happened upon this book when browsing for Ethiopian cookbooks at IndyPL.

Unlike the doro which called for very finely diced onion, Tsehai calls for straight-up onion paste.4 I achieved this using the small side of my box grater. Like the doro, though, she calls for the onion to be cooked initially without any oil.

After dry-frying the onions slowly to caramelize them,5 we add in the berbere, a diced tomato, tomato paste, ginger, and garlic.

The resulting paste is cooked over low heat for ~10 minutes to help the flavors develop. Then, rinsed (not soaked) lentils are added. This is where the technique was most interesting to me. I'm used to adding lentils along with plenty of water for cooking and just walking away and letting it simmer.

According to Tsehai, since consistency is such a core tenet of Ethiopian cooking, cooks will tend sauces while they cook to ensure they develop the correct consistency. This technique is reflected here -- we are instructed to add water 3 tablespoons at a time, only as it is absorbed by the lentils, to maintain the correct consistency.

All told, this took about 4.5 cups of hot water added over the course of about 45 minutes until the lentils had cooked to the correct done-ness. Despite the more-involved nature of the cooking, I really liked this approach. It let me add more water based on how much longer the sauce needed to cook, rather than cooking the sauce longer because the water needed to evaporate.

I served the misir with some injera flatbread. The resulting sauce is spicy, yes, but I continue to be amazed at how well the techniques take the edge off of the spice and blend it into the dish. I really liked the misir; it's probably my favorite of the Ethiopian dishes we've tried so far, and definitely one I'd make again on a week night.

As for my technical shortcomings, I primarily wish I'd caramelized the onions longer. I'd like to try this recipe again, but play with the spices. Yohanis Gebreyesus, author of the cookbook I used for the last two weeks, includes a recipe for misir that uses much less berbere but leans more into other earthy spices like nigella and mekelesha blend.

Fusion Zone

Disclaimer

What follows makes no attempt at replicating traditions or customs, and is my own sacrilegious doing.

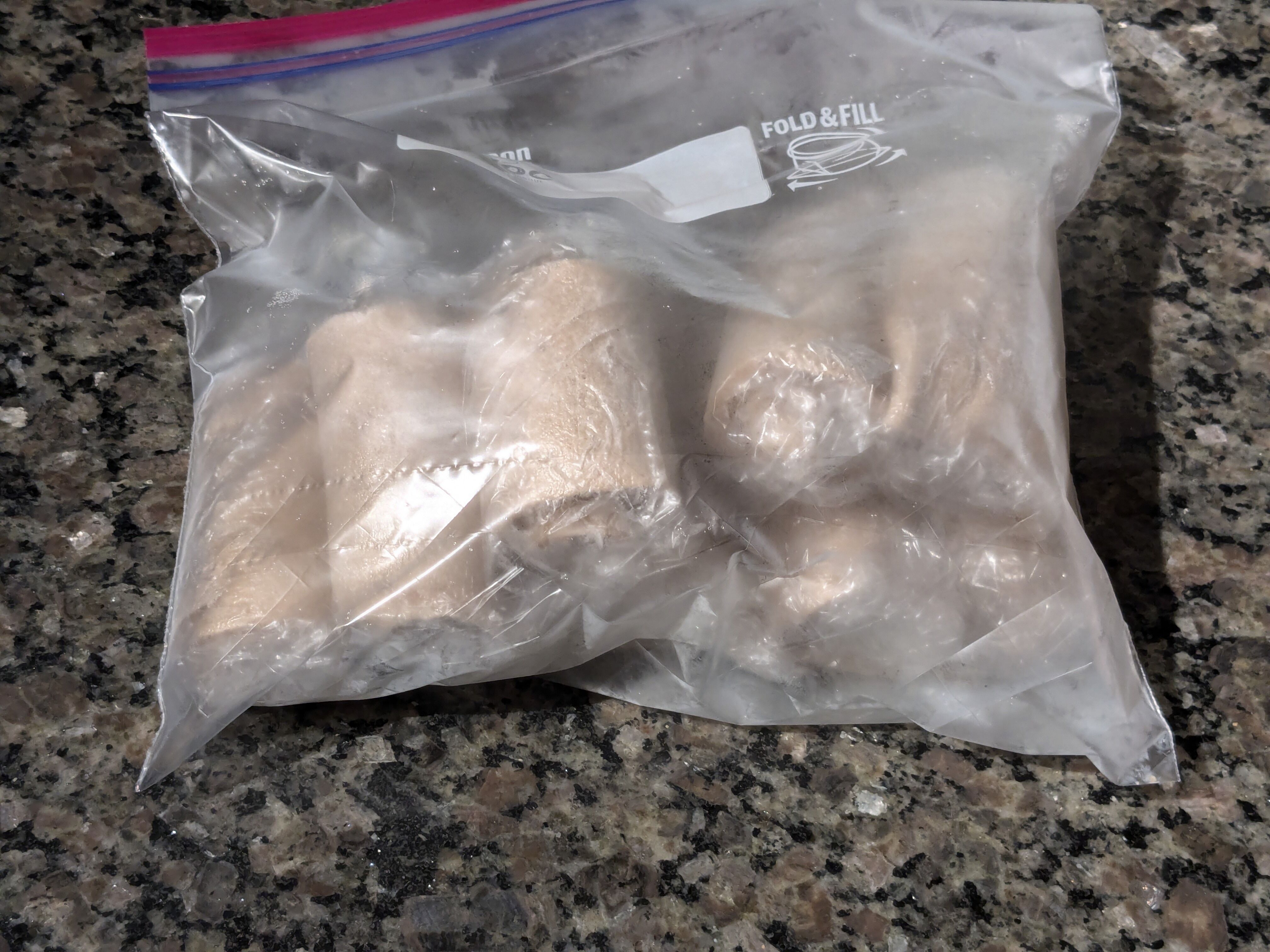

The first week of our Ethiopian exploration, I visited my local Ethiopian restaurant and convinced them to sell me some full-size injera, which they graciously did.

There was no way I was going to finish all the injera before it spoiled, and I wanted to have some for later weeks, so I decided to try freezing it. I did this by cutting it into strips, rolling it up, and plastic-wrapping each roll. Then, a couple of hours before dinner, I removed 6 or so rolls and let them thaw.

It's not perfect, and the thawed injera is a bit less flexible than its fresh counterpart, but I was surprised at how well it worked.

(Also, I ate the leftover misir for lunch over white rice -- highly recommend.)

All images in this post were taken by me. I borrowed "Auntie Tsehai Cooks: A Guide to Making Authentic Ethiopian and Eritrean Cuisine" from the fantastic Indianapolis Public Library.

Footnotes

-

I've seen this as wot and wat. The recipe I used for the doro spelt it wat, but our author this week spelt it wot, so I decided to go with her spelling herein. ↩

-

It's not traditional, but here I'm using the blend of lentils I keep on hand. My favorite: 25% masoor dal (red lentils), 25% moong dal (mung beans), and 50% chana dal (chickpeas). ↩

-

If you were curious, 1 cup of onion paste took 1 large onion plus 1 very small onion. ↩

-

Tsehai recommends doing this separately, in a large batch, and freezing the caramelized onion paste. ↩